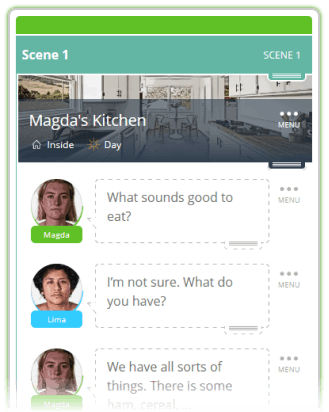

With one click

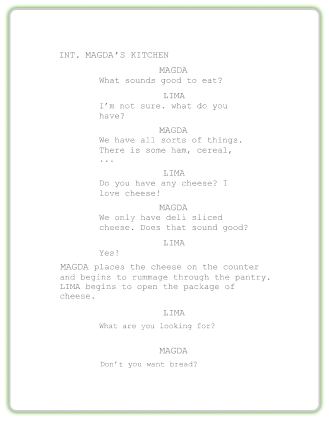

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

Culture is the driving force behind people's flawed nature and peculiarities in both fiction and real life. We often think of culture as 'surface' phenomena, like clothes we wear and specific cultural festivities or sporting events. But it goes far deeper than that. The culture we are born into profoundly shapes how we perceive the world around us — even if we don't realize it. It distorts the lens through which we experience life and influences our philosophies and behaviors.

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

Take, for example, the extreme differences between Western culture and remote cultures. In the West, cannibalism is reprehensible. But in Papua New Guinea, eating the dead is a funeral rite of endearment. Americans routinely consume billions of kilograms of beef in meals and fast-food restaurants, whereas, in India, cows are sacred. With these vast differences taken into consideration, it should come as no surprise to learn that our models of the world are influenced by culture. And that culture, in turn, influences how stories are formed.

All human societies we know of tell stories in one form or another, either orally or written down. The role of stories, cross-culturally, appears to be a way of incorporating cultural norms and lessons and helping people work out what they need to do to control or restore order to a particular environment.

Storytelling is almost always dictated by adults, who use the vessel of a story to tell children what is and isn't fair in life, what's valuable and what isn't, and reinforce how good standing citizens should behave. As a result, stories often teach moral lessons, dole out punishments and rewards, and do so in a way that reflects the culture of their origins. And stories are often tweaked, with the adults (storytellers) adding in their own narrative messages.

As we grow up, our brains are in a state of developing plasticity. Our brains absorb information from the world around them, and what they see shapes their neural pathways. This neural shaping, it is believed, is especially prominent in the first seven years of life.

As Western children grow up, they are raised to see themselves as individuals in a culture of individualism. This perception of the self in the world is a unique quirk that is thought to have begun around 2,500 years ago in Ancient Greece. Westerners also tend to see life through a series of choices and personal freedoms and to view the world as made up of individual parts and pieces.

According to some psychologists, the model behind Western storytelling is a product of Greece's rocky and hilly landscape — which wasn't much suited for large-scale agriculture. Therefore, success in Ancient Greece required hustling it out on your own through various small business types, such as fishing, selling tanning hides, or making olive oil.

For the Greeks, therefore, a measure of self-reliance was the key to success. And individualism was paramount to mastering the terrain around them. It's not a perfect theory, but it's undoubtedly fascinating — and could explain how the 'individual' arose in the West, starting with the Greeks.

Unsurprisingly, the Greeks began to laud the all-powerful individual as a cultural focal point. They also lauded personal glory, perfection, and progress. After all, the Greeks created the legendary competition that pitches the self versus the self, which we still know today as the Olympics. The Greeks also practiced early forms of democracy and individual voting rights, and in their mythology, told fables about Narcissus and the dangers of self-love.

Above all, the main message was that, through progress and self-determination, the individual could be the champion of their own destiny and power and choose the life they wanted. With these values enabled, the individual could shake off the shackles of slave-masters, tyrants, and even God.

Things are a lot different in the Far East. China, the mother culture for Korea and Japan, is on the far side of the Eurasian continent and separated by mountains and deserts. For the Greeks, any semblance of Chinese civilization was probably just rumors and whispers from traders and travelers on the silk roads.

China's wide-open spaces and fertile agricultural landscape couldn't have been more opposed to the state of affairs in Greece. The feasibility of huge agrarian fields favored large group endeavors at the expense of the individual. Success probably meant fitting in and getting your head down with a large community on a rice or wheat irrigation project in China. Survival was bolstered by teamwork and reliability rather than small business projects. This theory, understood by some psychologists, is known as the 'collective theory of control.' And it is believed geographic factors like this led to China and the Far East's collective ideal of the self.

China's most famous philosopher, Confucius, seems to back up these collective ideals in his writings, describing the superior man as "one who does not boast of himself but instead prefers the concealment of his virtue as he should cultivate a friendly harmony and let the states of equilibrium and harmony exist in perfection." This is all in stark contrast with the utterances of the philosophers in Ancient Greece.

For Easterners, successful control of the world was through group effort, which also shaped how the Chinese came to perceive reality. To them, existence is a field of interconnected forces — and not individual pieces and parts perceived by the Greeks. And out of these wholly different outlooks of reality come different types of stories.

Greek myths usually have three acts, or what Aristotle labeled a 'beginning,' 'middle,' and 'end,' which are also sometimes known as the phases of 'crisis,' 'struggle,' and 'resolution.' Greek myths also usually feature a singular hero as the main protagonist, who through the course of his journey battles monsters and overcomes enormous obstacles to return home with treasure eventually.

Or in other words, Greek myths embodied the Greek ideal of the individual, usually a courageous person who could change everything if only he put his mind to it. Stories like this influence Western minds in early childhood, and some studies have shown that, when asking children to make up a story, they tend to follow the Greek model subconsciously from a young age.

China's outlook is very different. For example, there are virtually no autobiographies present in Chinese literature up until the modern day. And when they do come out, they tend to be stripped of voice and opinion and told almost from the point-of-view of a bystander reflecting on a life, rather than directly from the person telling it.

Likewise with fiction, rather than following a straightforward cause and effect pattern, Eastern stories tend to take the form of many different characters, all reflecting on the plot's drama and often in contradictory ways. The effect is to try and place the reader in a position where they have to decipher and tease out what really happened on their own.

An excellent example of this is 'In A Bamboo Grove' by Ryunosuke Akutagawa. In this story, a victim is murdered, and the event itself is recounted from several witnesses, including a spirit channeling the victim itself. It is rare for there to be a clear, unambiguous ending or real closure in Eastern stories. Happy ever afters are not familiar tropes in Eastern literature. Instead, the reader has to decide for themselves, and this is how Easterners tend to derive pleasure from the story.

In the few tales of Eastern origin that do focus on individuals, heroic deeds tend to be achieved in a group-like manner. In Western tales of heroism, the hero is pitted against evil, truth prevails, and love conquers all. But in Asia, heroism is achieved through sacrifice, especially if that sacrifice helps protect and take care of the family and the community.

The Japanese have a form of storytelling known as kishotenketsu. It typically has four acts. In act one, we are introduced to the characters. In act two, the drama begins. Act three usually involves a twist or something surprising. In the final act, the reader is invited in an open-ended way to try and look for harmony between all of the story parts.

One of the things that perplex Western readers the most about Eastern-origin stories is that the ending is often ambiguous. That is because, in Eastern philosophy, life is generally seen as complicated and without clear answers.

Readers in Eastern cultures take pleasure from the narrative pursuit of harmony. In contrast, Westerners enjoy accounts of individuals struggling to achieve victory against all the odds. The differences in these stories reflect the different ways that both cultures understand change. Westerners see the world as made up of tameable fragments that need to be put back together whenever drama or unexpected change arises in a story. For Easterners, life is a field of forces that all interconnect. When the drama happens, the desire for the Easterner is to try and restore these life forces back into harmony so that they can all co-exist.

And while both East and West tell different types of stories, the underlying purpose is the same. Both Easterners and Westerners tell stories as lessons in control. They are designed to help people orientate themselves, to find their place in the world. Stories everywhere, it seems, are attempts to reign in the chaos. They are ways of managing the bewildering external reality of the world around us.

Neil Wright is a copywriting executive for a UK-based transcription company called McGowan Transcriptions. His main hobbies include writing and reading. He is currently working on his first novel 'Poetic Spaces.'